[W]hoever shall indifferently perpend the exceeding difficulty, which either the obscurity of the subject, or unavoidable paradoxology must often put upon the Attemptor, he will easily discern, a work of this nature is not to be performed upon one legg; and should smel of oyl, if duly and deservedly handled.

Sir Thomas Browne, ‘To the Reader,’ in Pseudodoxia Epidemica, (1646)

Thus warns the English polymath Sir Thomas Browne, at the opening of a treatise in which he sets out to discover truth via a thorough consideration of errors: on the path lies ‘unavoidable paradoxology’. In Su Friedrich’s films, a will to articulation meets a refusal to flatten ambiguity. The unavoidable paradoxes – and unavoidable difficulty in grappling with them – that these convictions engender are embraced with frankness and curiosity. Friedrich’s observations on the effect of her Catholic upbringing on her filmmaking approach exemplify her willingness to sit with contradiction. In a 2019 lecture on her filmography, titled ‘How to Drag Your Private Life, Kicking and Screaming, Into the Public’, Friedrich outlines some principles of her filmmaking ethic, listing among them, ‘I don’t preach’. She explains: ‘I was raised Catholic, and heard many sermons on Sunday, and while those might be appropriate in a church, I don’t think they are useful in a work of art’. This sits curiously beside a 2004 interview with Jane Cutler, in which Friedrich conversely observes:

When I make art I do feel that sometimes I’m exhorting people to deal with themselves or deal with a situation. [...] I think that’s kind of like sermonizing, but I didn’t make the connection until a few years ago between my childhood experience of listening to the weekly Sunday sermons and this impulse I seem to have to exhort people to look seriously at their lives.

So, Su Friedrich doesn’t preach – and she does. I suggest that it is not only that these statements were made 15 years apart, though, of course, they were, and conceptions do change over such spans of time, but that both points articulate a truth about the way Friedrich’s works act on a viewer. The films themselves often circle ideas in this way; walking all the way around a subject, gaining proximity to truth by welcoming apparently irresolvable contradictions along the way. The present programme selects two such works: Sink or Swim (1990) and Seeing Red (2005), each of which takes on a rigorous formal approach to articulate something of the filmmaker’s life experience. Sink or Swim is a stubbornly complex portrait of a clever, careless, complex father, and a daughter (Friedrich) formed by his behaviour. Seeing Red takes on the frustrations of an artist’s midlife with an irrepressible multiplicity of attitudes, including but not limited to fury, anxiety, and good humour.

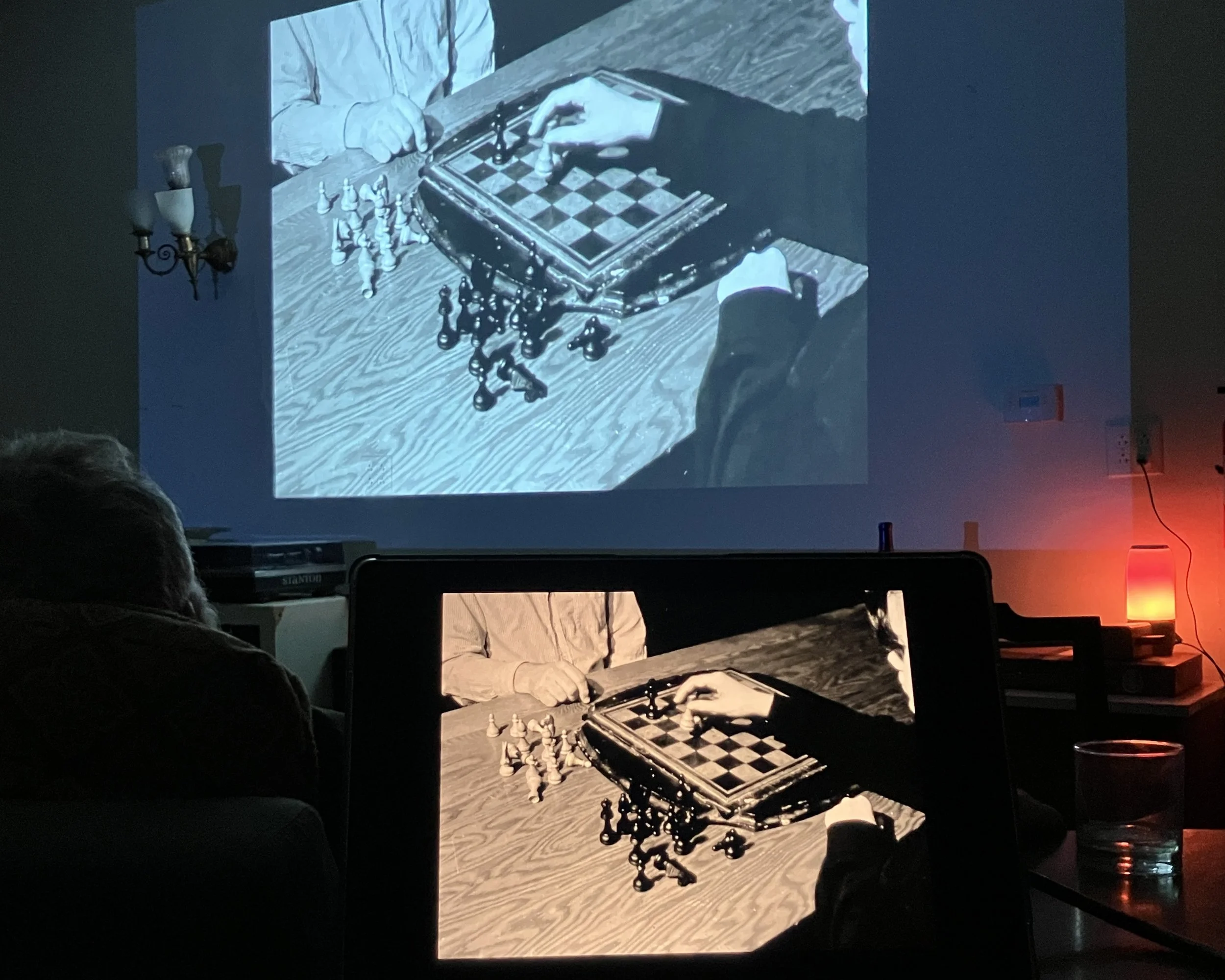

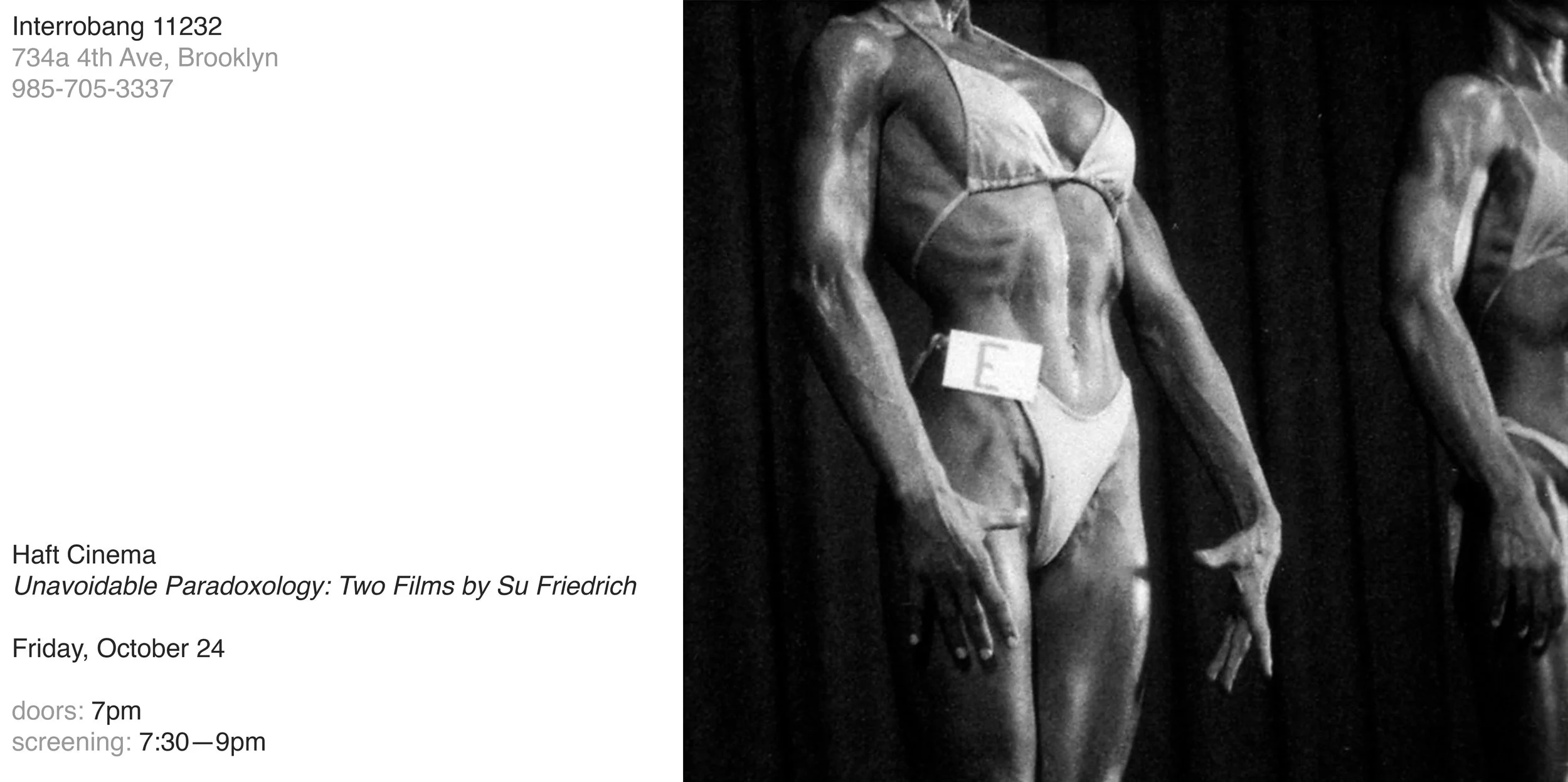

Sink or Swim is shot on gritty black and white 16mm, and takes the form of 26 vignettes, each with a subtitle corresponding to a letter of the alphabet, which is presented in reverse alphabetical order. The film’s title refers to an event detailed in a section titled ‘Realism’. Like nearly every vignette, ‘Realism’ is narrated in the third person, in the voice of a child with a miraculous knack for enunciation. We learn that when ‘the girl’ asked her father to teach her to swim, his response was to bring her to a pool, explain the theory and mechanics of swimming, and throw her into the deep end. The incident is blatantly harsh on the part of the father, but, under Friedrich’s hand, it does not read as unambiguously cruel. After some thrash and struggle, the girl takes to the water and ‘from that day on, was a devoted swimmer’. The film proliferates with stories like this: we learn that the father taught her to play chess, then refused play with her ever again when she wins for the first time; that he once took her on a trip to Mexico, only to fly into a fit of misplaced jealousy toward a young boy she befriends, and send her home, alone. In articulating her experiences of her father’s flawed parenting, Friedrich works hard to preserve the complexity of his character. As she unfurls details of both her father’s traumas and her own strengths, Sink or Swim emerges as far more than the simple indictment it easily could have been. At the heart of the film is an understanding that the truth of experience is busy with unavoidable paradoxology.

Through much of Sink or Swim, we rest in the plausible deniability of the film’s third person narration, until a section titled ‘Ghosts’ jolts us out of it – not into the first person (‘I’), but the second (‘you’). ‘Ghosts’ is also the only vignette to feature sync-sound audio: instead of the narration we have by now grown accustomed to, the section invites the viewer to read along as Friedrich types out a letter addressed to her father. The shift from audible narration to words on the screen, accompanied by the click-clacking of Friedrich’s typewriter; from the storylike ‘she’ to that infinitely loaded pronoun, ‘you,’ is a splash of cold water, cracking open questions inherent to the autobiographical form about perspective and privacy.

***

In an 2008 essay titled ‘Seeing (through) Red’, Friedrich writes:

For thirty years, I’ve worried about what it means to use private experiences – my own and those of people close to me – as subject matter. [...] Can the teller ever describe experiences they’ve shared with others without creating huge gaps, falsities, or errors gross and small?

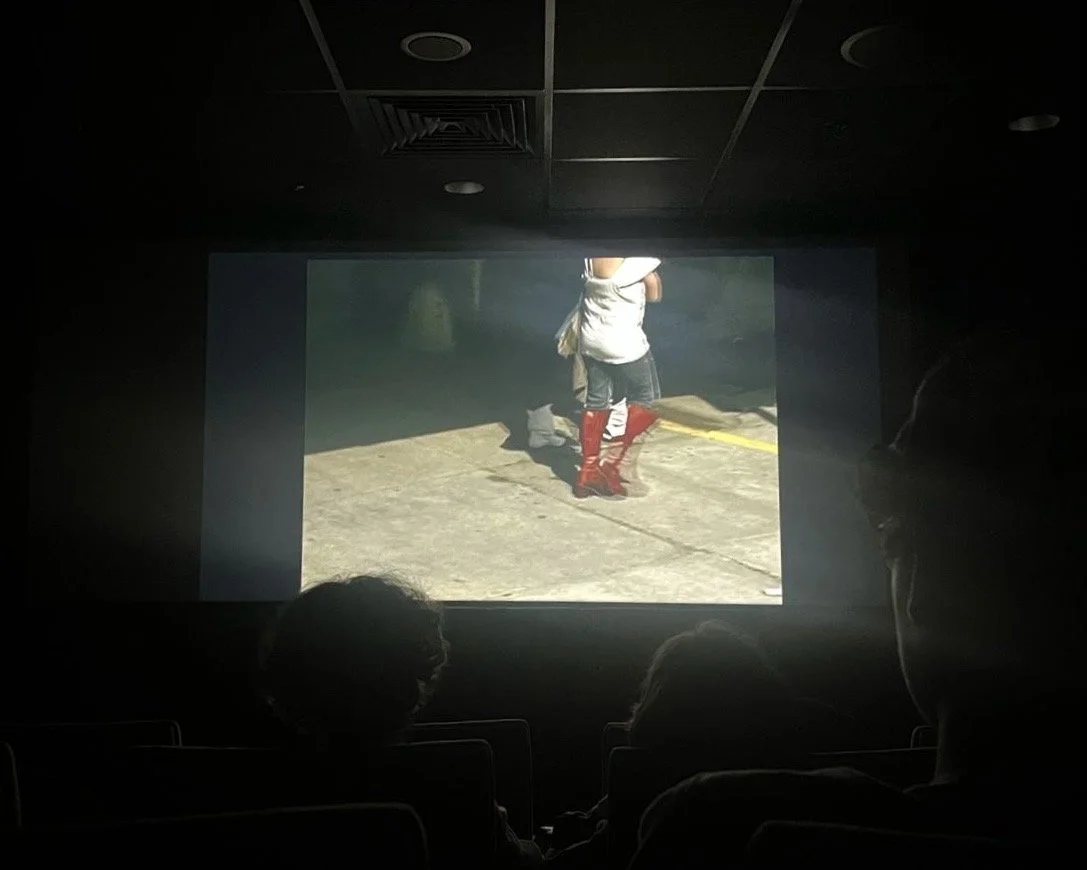

Seeing Red is, among many things, a reflection on the perils and paradoxes of autobiographical artistic process. It is shot on video, and its title, idiomatic of fury, tips us off as to the quality of feeling to which we will bear witness through a series of diaristic considerations; complaints; and confessions from Friedrich. Beyond the idiom, the title is also a literal description of the film’s primary visual conceit: an I-spy assemblage of red things in the filmmaker’s Brooklyn neighborhood: red scooters, red shoes and red sweaters; red icees; red hair; red signage; red backpacks and red birds; red graffiti; and red tulips all feature. This exercise overturns a piece of technical advice Friedrich herself gives to filmmaking students, that ‘red doesn’t look good on video’.

In between the scavenger hunt for glaring red, we see clips of Friedrich’s torso (clad variously in red and orange clothing), as she records diary entries. In these, she grapples with the anguish of a 50-something-year-old self-professed ‘control freak’, trying to be a good friend; a good lover; a good filmmaker, a good teacher. We see her burst into tears — and question the troublesome performativity of crying on camera (prescient, in a film shot the year of YouTube’s founding).

Music is always important in Friedrich’s films, and Seeing Red is no exception. The score, Bach’s Goldberg Variations performed by Glenn Gould, joins the kaleidoscope of red in tipping us off as to a thesis of sorts: by persistently engaging with variations in articulation, we might preserve the unavoidable paradoxology of the experiences we hope to describe, thereby avoiding or diminishing those ‘gaps’; ‘falsities’, and ‘errors’ Friedrich writes of.

This is not so easily done. For Sir Thomas Browne, grappling with paradoxes and pursuing truth ‘should smell of oil’ (a reference to the burning of oil lamps), and will not be ‘performed upon one leg’, – which is to say, it will require a long and strenuous effort, and not be flippantly achieved. Friedrich, who frequently emphasises the labour-intensive process of editing in both film and video, knows this as well as anyone, and takes on the task with more gusto than many. That Browne deploys these figures of speech to describe the difficulty of paradox-attentive truth telling belies the fact that a commitment to articulating complex ideas also demands deft and creative use of language.

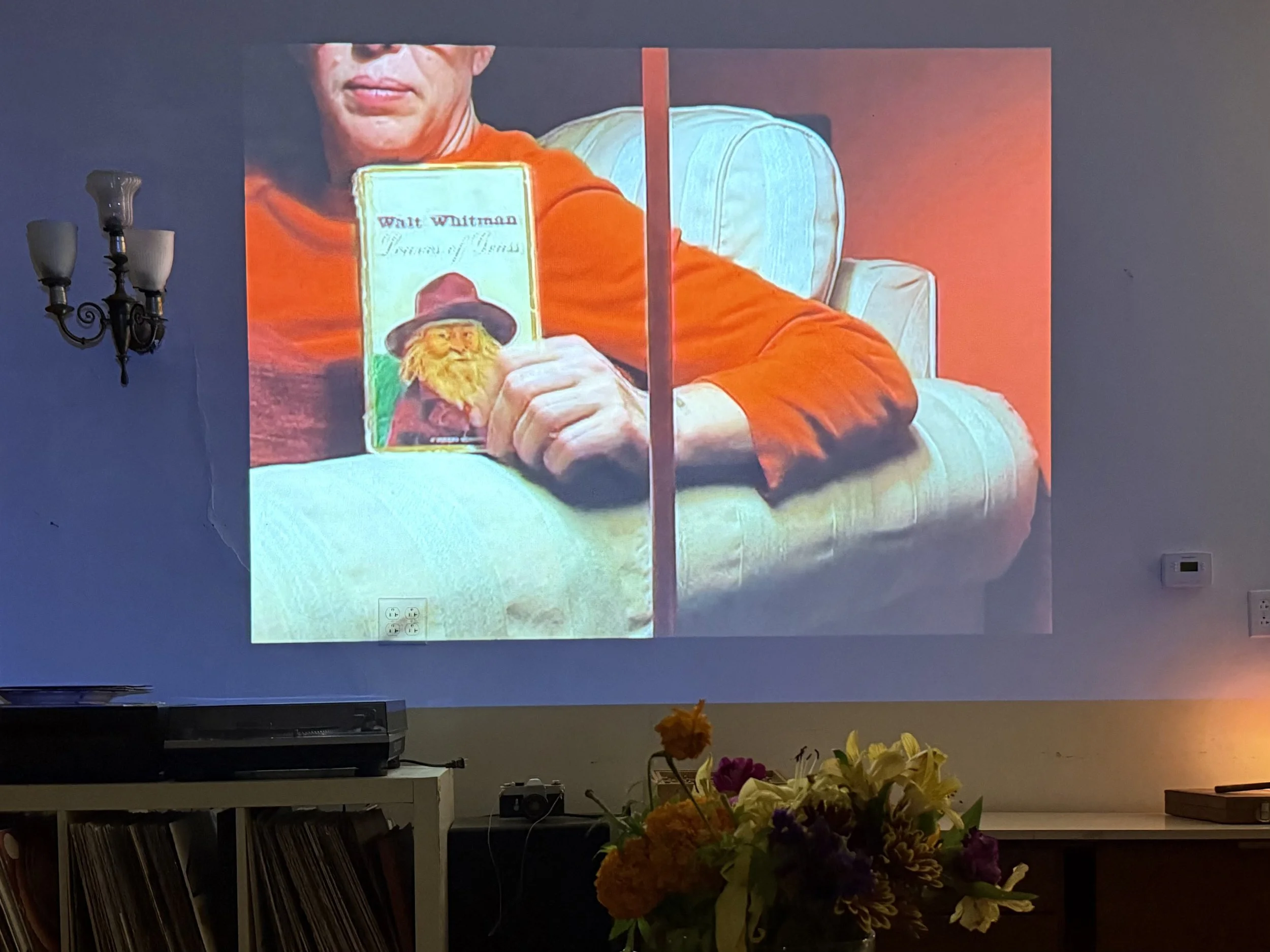

In Friedrich’s work, language – in the form of dialogue or monologue; audible narration or on-screen text, or otherwise – is frequently an important tool; a possible bulwark against oversimplification, if well deployed. Seeing Red plays with language severally, with references to titans of 19th-century American verse contributing to the play of ideas. In one instance, she goes to read from a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and finds a note she had scrawled on the book’s frontispiece decades earlier: ‘nestled in the crook of my arm, where the sweat creeps on a summer day.’ This, she reads aloud, twice. First with the wistful voice it requests, and it conjures a bucolic image. Then, with more than a bit of self-mocking, she reiterates: ‘I guess I carried this in the crook of my arm, where the sweat crept on a summer day. Oh goodness’. It is as concise an encapsulation as any, of the many lives a sentence can live.

When she does read from the Whitman, a poem titled ‘O Me! O Life!’, Friedrich’s voice is overtaken and drowned out by the Variations, while on-screen text persists in the effort of delivering the lines. The following is presented us in the fullness of its questioning, notably sans the ‘Answer’ that Whitman goes on to provide:

Oh me! Oh life! of the questions of these recurring,

Of the endless trains of the faithless, of cities fill’d with the foolish,

Of myself forever reproaching myself, (for who more foolish than I, and who more faithless?)

***

Another hero of 19th-century American letters writes:

‘I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience.’

Thus reads Thoreau’s classic apology for autobiography, which opens Walden. What resonates in these lines is the paradox they observe: accurate as Thoreau may be in assessing the ‘narrowness’ of his experience, we know too that it is precisely from the exquisite range of experience an individual may have that autobiography gains resonance. It is also by virtue of this exquisite range that autobiography risks exposing the depth of one’s own misunderstanding or enshrining in the mind of its audience the ‘errors’ to which Friedrich is so alert.

Thoreau’s apology for autobiography is the epigraph to From Root to Flower (2004), a collection of poetry by Su’s father, Paul Friedrich, to which (along with other works of his) she makes reference in Sink or Swim. The discomfort of being misunderstood is a persistent undercurrent in the film, and one brought out by Friedrich’s engagement with her father’s autobiographical poems. These sharply reveal schisms between their experiences, and the extent of his failure to perceive or understand her feelings. One such instance unfolds over sequential sections titled ‘Flesh’, and ‘Envy’, which detail the aforementioned disastrous trip to Mexico, and Su’s discovery, 10 years later, of a poem her father wrote about sending her home. The poem closes with the declaration ‘Your eyes at our parting condensed all children orphaned by divorce / A glance through a film of tears at a father dwindling to a speck’, to which the narration in Sink or Swim responds:

‘he still didn't realise that he had been acting like a scorned and vengeful lover and that hers had not been the tears of an orphaned child, but those of a frustrated teenage girl who had had to pay for a crime she didn't commit’.

Friedrich, whose autobiographical films move with rigorous, almost compulsive determination to preserve paradoxical truth, knows intimately the discomfort of featuring in somebody else’s autobiographical project.

Sink or Swim works to make sense of a childhood, and in so doing, succeeds in weaving an uncompromisingly complex portrait of a family dynamic where a more straightforward tale of a family wrecked by a domineering, careless father would be possible. Seeing Red reflects on the mechanics of how such preservation of paradox can be achieved by variation in articulation. The dogged pursuit of complexity these films exhibit is one tactic against the threat of being rendered oversimply (and the crime of rendering another so). Still, a subtle alternative, entertained if not enacted, slowly emerges between the films: paradoxical truth can be sketched out through a proliferation of articulation, certainly. Or, it can be preserved via intense privacy.

Brief instances in each film suggest what it might mean to vanquish the threat of being misunderstood by simply removing the opportunity for others to form an understanding of you, whatsoever. Three-quarters of the way through Seeing Red, Friedrich prepares to film another diary entry when, concerned she might be overheard by someone in the next room, she resolves to wait until she can be certain of privacy. It is a fascinating moment, as we the audience are reflect on the access to Friedrich’s inner world we have perhaps taken for granted up to this point – and on the editorialising that has taken place in what is being presented us.

In Sink or Swim, the section titled ‘Journalism’ has a similar effect. It includes an anecdote of privacy invaded: ‘the girl’ is gifted a diary – complete with a lock and key – and on its first page, scrawls the declaration, “if anybody reads this diary, they are very mean. It is personal.’ When her parents eventually divorce, ‘the girl’ keeps this secret from all of her friends, but eventually writes about it in her diary. She writes in pencil, as opposed to her preferred pen, and later returns to find the entry about her parents divorce has been erased. ‘Her mother was the only possible suspect’. These scenes adumbrate a road not taken, an alternative to the proliferation of variation which Sink or Swim employs and Seeing Red celebrates: avoidance of articulating oneself publicly altogether, in favour of silent, uninterpretable privacy. One cannot help but think of Dickinson’s ever-striking lines, ‘That polar privacy / A soul admitted to itself— / Finite infinity.’ Of course, this possibility is eclipsed by the very fact of the films, but is stubbornly, paradoxically, present nevertheless.

In the final moments of each film, we are met with the cardinal opposite of silent privacy: confessional cacophony. Seeing Red ends with Friedrich spinning on an office chair, removing the layers of clothing we have seen her wear over the course of the film. As she does, audio from the various diary entries is layered over one another, in a churn of ideas further whipped up by Bach’s 14th Variation. At the close of Sink or Swim, Friedrich’s own voice supplants the young narrator for the first time, and she sings the alphabet (forwards). Her singing loops over itself to form a chorus, before eventually resolving back into one voice, that moves, again, into the confronting second-person to utter the request: ‘tell me what you think of me.’

—

October 01, 2025

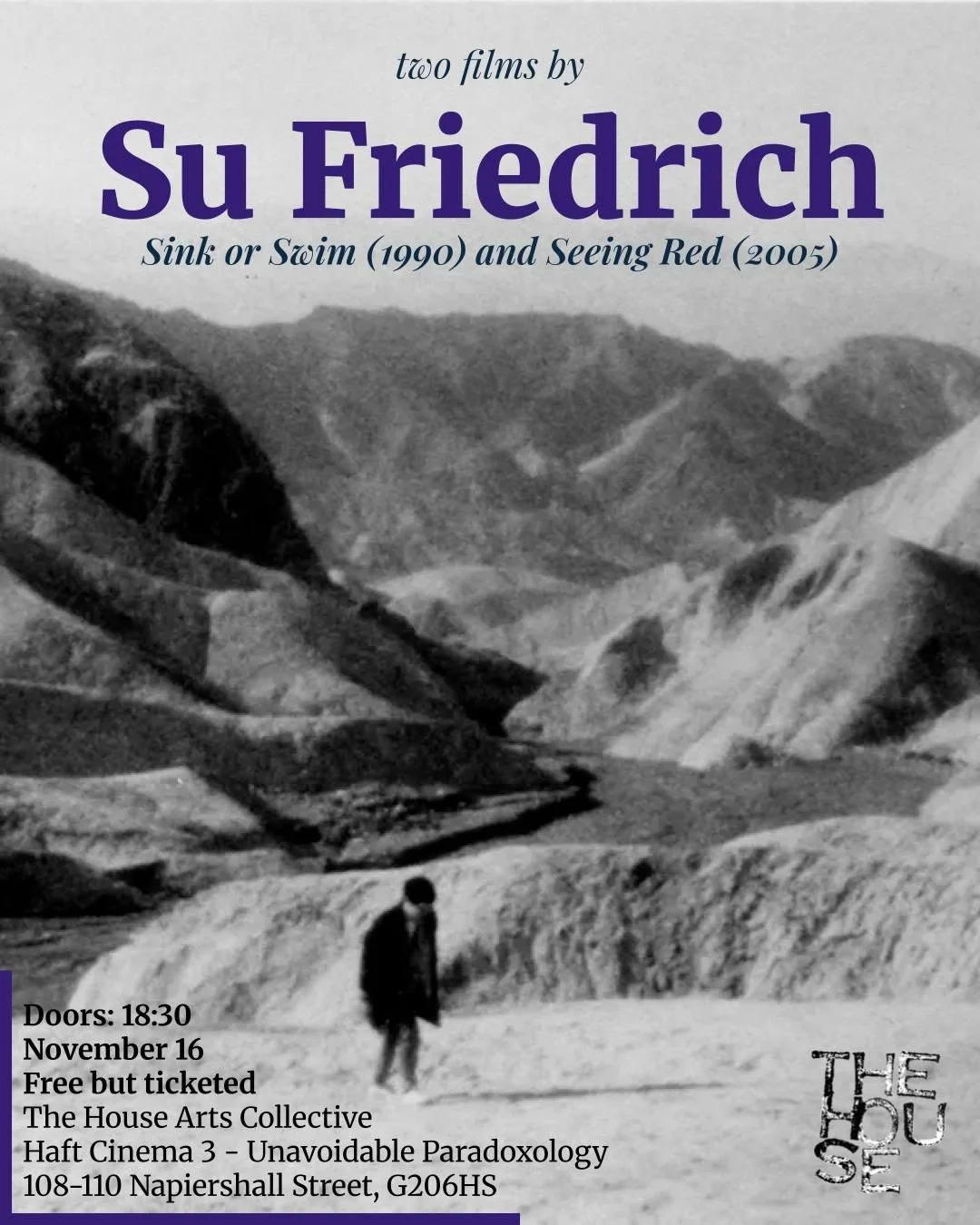

HAFT CINEMA III

Unavoidable Paradoxology: Two Films by Su Friedrich

programme

SINK OR SWIM Su Friedrich | 1990 | 70 min

SEEING RED Su Friedrich | 2005 | 27 min

total runtime: 97 min

INTERROBANG 11232

@interrobang11232 / www.interrobang11232.com

Brooklyn, NY, U.S.A.

October 24, 2025

ARTS LETTERS & NUMBERS

@artslettersandnumbers / www.artslettersandnumbers.com

Averill Park, NY, U.S.A.

November 07 2025

HOUSE ARTS COLLECTIVE

@thehouseartscollective

Glasgow, Scotland

November 16 2025

MIA’S APARTMENT

@miaswu

Los Angeles, California

November 22 2025

[private screening]

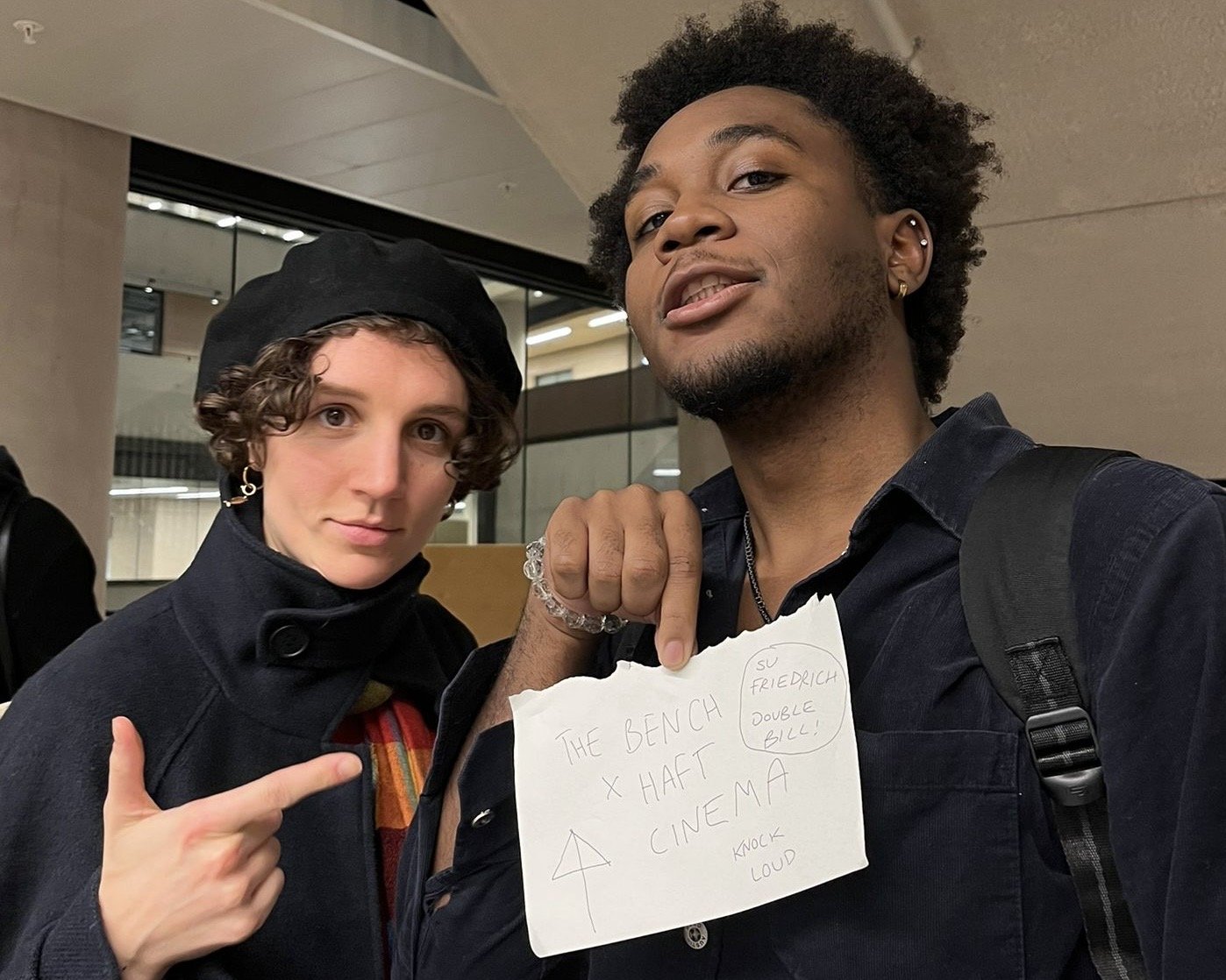

THE BENCH COLLECTIVE

@the_bench_collective

London, England

November 24 2025